Asynchronous messaging is a communication method, where the sending party (also known as producer) can send a message and continue with its unrelated tasks without waiting for an immediate response from the other party (aka consumer). Unlike the synchronous request-response communication model (e.g., RESTful web services), this method eliminates the need for both communicating parties to be up and running at the time of communication. Usually, a message is placed at a third-party communication entity so that the interested subscribers can receive the message. This makes the message producer completely independent and decoupled from message consumers. It does not need to know who the consumers are, whether they are active at the moment of communication or their addresses. It just needs to know how to reach the third-party entity to store the messages.

This third-party communication entity is known as a Message Broker. A message broker is an intermediary software module that applications and services use to communicate with each other for information exchange. Message brokers can be used to validate, store, route and deliver messages to the required destinations. They serve as intermediaries between different applications and services, allowing senders to issue messages without knowing where the receivers are or how many of them there are. This facilitates decoupling of processes and services within systems.

Message brokers also facilitate interoperability by translating messages from the formal messaging protocol of the sender to the formal messaging protocol of the receiver. This allows interdependent services to “talk” with one another indirectly, even if they were written in different languages or implemented on different platforms.

Message brokers are software modules within messaging middleware or Message-Oriented Middleware (MOM) solutions. This type of middleware provides developers with a standardized means of handling the flow of data between an application’s components so that they can focus on its core logic. It can serve as a distributed communications layer that allows applications spanning multiple platforms to communicate internally.

In order to provide reliable message storage and guaranteed delivery, message brokers often rely on a substructure or component called a message queue that stores and orders the messages until the consuming applications can process them. Message queues store messages in the exact order they are received and sent to the receiver in the same order. This is based on a FIFO (First In, First Out) queue data structure. Enqueued messages remain in the queue until receipt is confirmed. If for some reason a message was unable to be delivered (e.g. problem with the network), the message delivery will be rescheduled for later. Brokers typically use a dead-letter queue (DLK) as the queue to which messages are sent if they cannot be routed to their correct destination.

Message brokers may comprise queue managers to handle the interactions between multiple message queues, as well as services providing data routing, message translation, persistence, and client state management functionalities.

The most common queue-based message brokers are RabbitMQ and Apache ActiveMQ. There are also managed message queue services such as Amazon Simple Queue Service (SQS) and Azure Service Bus.

Messaging Patterns

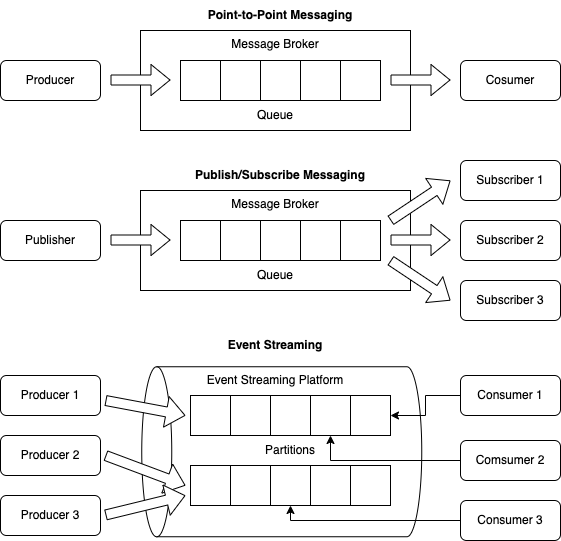

Message brokers offer two basic message distribution patterns or messaging models:

Point-to-Point Messaging

Point-to-Point (P2P) is the distribution pattern utilized in message queues with a one-to-one relationship between the message’s sender and receiver. Each message in the queue is sent to only one recipient and is consumed only once. Multiple producers can send messages to the same queue and multiple consumers can read from it. However, when a consumer processes a message, it’s locked or removed from the queue and is no longer available to other consumers. P2P messaging is used when a message must be acted upon only one time. Examples of suitable use cases for this messaging style include payroll and financial transaction processing. In these systems, both senders and receivers need a guarantee that each payment will be sent once and once only.

Publish/Subscribe Messaging

In Publish/Subscribe (pub/sub) message distribution pattern the producer of each message publishes it to a topic, and multiple message consumers subscribe to topics from which they want to receive messages. All messages published to a topic are distributed to all the consumers subscribed to it. This is a multicast-style distribution method, in which there is a one-to-many relationship between the message’s publisher and its consumers.

Generically speaking, there are two types of subscriptions:

- An ephemeral subscription, where the subscription is only active as long the consumer is up and running. Once the consumer shuts down, their subscription and yet-to-be processed messages are lost.

- A durable subscription, where the subscription is maintained as long as it’s not explicitly deleted. When the consumer shuts down, the messaging broker maintains the subscription, and message processing can be resumed later.

Hybrid Model

With message brokers that support pub/sub, topics and queues may be used in a composite manner. Message producers can publish to topics and then those messages are routed to physical queues that are not shared between applications. This decoupling of publishing to consumption is powerful and makes an architecture easy to evolve and customize. Messages can be published to topics without forcing any grouping of events. A separate topic can be used per event type so that each event is published to its corresponding topic. The routing to queues is not fixed and can be changed without impacting other applications. This gives developers a lot of freedom to evolve and change their architecture. Additionally, each application can get relative ordering of any arbitrary set of events, thus avoiding many pain points that can occur in an event-driven architecture.

Log-based Message Brokers

Log-based message brokers, as the name implies, store messages by appending entries to a “log file” (logically, not necessarily stored in a single physical file). Log is persistent storage and a shared resource, which allows multiple consumers to read from it in parallel. Each consumer works at its own speed and reads the message from a different position in the log, without removing the data (data is removed after a configurable amount of time). It makes them independent from each other and more decoupled from the broker. Another advantage is that multiple consumers can work with a single log, so there is no need to create additional entities for that purpose as in the case of queue-based brokers.

Event Streaming

Log-based message brokers enable the processing of event streams. An event stream is a continuous flow of data, where each element contains information about an event or change of state. Events only describe what has happened, but they do not specify the action that should be taken. The stream is unbounded, meaning it has no real beginning and no real end – each event is processed as it occurs (usually near real-time) and managed accordingly. Events (within a topic) are ordered, typically based on a relative or absolute notion of time. Each event in a stream carries a timestamp that denotes the point when the event has occurred.

Event streaming is based on the pub/sub messaging pattern. Multiple event producers publish events to a topic as messages. A topic is typically a categorization for a particular type of event. Subscribers interested in events of a particular category subscribe to that topic. As events are published to the topic, the broker identifies the subscribers for the topic and makes the events available to them. Publishers and subscribers need not know about each other.

For each topic, the broker typically maintains a partitioned log of messages. Each partition is an ordered, immutable sequence of records, where messages are continually appended. Producers can control how events are distributed among partitions based on one of the attributes of these events (partition key). Consumers consume events by maintaining an offset (or index) to these partitions and reading them sequentially. When multiple consumers read from the same topic (consumer group), the partitions of that topic are divided among the consumers in the group and each event is received by only one consumer in that group.

An Event Streaming Platform (ESP) is a highly scalable and durable system capable of continuously ingesting gigabytes of events per second from various sources. The data collected is available in milliseconds for intelligent applications that can react to events as they happen.

The most common log-based message brokers or ESPs are Apache Kafka, Amazon Kinesis, Google Cloud Pub/Sub and Azure Event Hubs.

Messaging Patterns

Messaging Protocols

The connection between messaging clients (producers/publishers, consumers/subscribers) and a message broker (provider) can be based on standard or proprietary protocols. The most common standard messaging protocols are:

- Advanced Message Queuing Protocol (AMQP) is an open standard protocol for MOM. It is designed to efficiently support a wide variety of messaging applications and communication patterns and ensures that implementations from different vendors are interoperable. AMQP is a binary application-layer protocol over TCP/IP.

- Simple (or Streaming) Text Oriented Message Protocol (STOMP), formerly known as TTMP, is a simple text-based protocol (similar to HTTP), designed for working with MOM. It provides an interoperable wire format that allows STOMP clients to talk with any message broker supporting the protocol.

- Message Queue Telemetry Transport (MQTT) is a lightweight pub/sub messaging protocol for MOM. It is designed for connections with remote locations that have devices with resource constraints or limited network bandwidth, such as in the Internet of Things (IoT). It is a binary protocol that runs over a transport protocol that provides ordered, lossless, bi-directional connections – typically, TCP/IP.

The message flow starts with a producer, which initiates a connection to a message broker and sends a message onto a queue or publishes it on a topic. The broker acknowledges the receipt of the message (ACK), allowing the producer to continue with other tasks, while the message is being handled by the broker asynchronously. The connection between the broker and message consumers (receivers) can be either broker initiated or consumer initiated.

Broker initiated (push) models require the broker to know about existing subscribers (pub/sub) or recipients (P2P). This can be achieved either through static registration or a service discovery mechanism. In the push model, the broker determines when to send data to consumers based on its own logic. Consumers do not need to maintain state or implement special logic to coordinate amongst themselves.

In consumer initiated (pull) models, consumers need to be aware of the broker’s address. In the pull model, subscribers send a message to the broker when they want to receive events, and only then the broker sends them data. Subscribers need to maintain the state to know what topics exist and what data to ask for (for example: where to read from in a particular topic).

Backpressure

Whenever a streaming pattern is used, events can be published faster than subscribers can process them. Buffering can be a temporary solution, but once the buffer is full, messages will be dropped. The system needs a mechanism to let the broker know that consumers cannot currently process more messages. Otherwise, either consumers or downstream services would suffer from resource exhaustion. This mechanism is commonly known as backpressure.

When consumers use a pull-based mechanism, the most common backpressure approach is pulling for events only when no events are actively being processed. This ensures systems downstream from the broker are not accumulating a backlog.

Push-based systems need a mechanism for subscribers to let the broker know that they cannot handle new events, sending an error instead of a normal ACK or temporarily pausing delivery. In addition to applying back pressure, many systems are also architected to dynamically increase their consumption and processing capacity when resource exhaustion is near. This ability to scale dynamically, combined with backpressure is fundamental. It prevents the system from suffering issues and/or outages and gives it time to provision capacity to handle the increased publishing rate.

Message Delivery

Another essential aspect of technologies implementing the pub/sub pattern is determining which subscribers get each message. The options are:

- All subscribers to a topic get all messages for the topic, which is useful for multicast use cases where each consumer needs to handle the message independently of other consumers, without the risk of creating conflicts.

- Only one of the topic subscribers gets a specific message. This model is commonly used for cases when multiple subscribers (“workers”) apply the same action, which should be executed only once per message, where there is no dependency between different messages. With this method, the system can increase the number of workers in order to increase parallelism and achieve higher throughput.

- Having subscribers grouped into “groups” and having all groups and only one subscriber per group get a message. The benefit is that it allows multiple processing actions to occur at different points in time and has many instances of each subscriber type per group to scale processing capacity. A drawback compared to the previous models is that it requires additional coordination mechanisms between brokers and consumers for group membership and group message processing.

Delivery Guarantees

Delivery guarantees or modes define how strongly a messaging system enforces the delivery of messages it processes. Each mode comes with a number of trade-offs. As it makes stronger guarantees about message delivery, the system needs to perform more checks and acknowledgments to ensure that messages are delivered, or maintain state to ensure a message is only delivered the specified number of times. This increases the latency of the system and reduces the overall throughput of the system. Each “real” message may require an additional 2-4 messages, and an equivalent number of additional roundtrips, before it can be considered delivered. The possible message delivery strategies are:

- At most once – In this mode, there is a potential loss of messages. A message is either processed once or not at all. This is the simplest of the guarantees to support, as the system doesn’t need to handle the processing of the same message multiple times. This mode can be used in scenarios where it is acceptable to lose messages (e.g., metrics).

- At least once – This mode is preferable if the loss of messages is unacceptable. The happy scenario is that a message is processed successfully once. But it is considered acceptable that it is processed more than once, so the system has to ensure that consumers can handle the same message arriving multiple times, by ignoring duplicate messages (idempotent consumers).

- Exactly once – This would be the best strategy but is the hardest to achieve and incurs significant per-message overhead on both the client, server and network. It requires not only a way to acknowledge delivery, but additional state on the sender and receiver to ensure that a message is only accepted once, and that duplicates are discarded.