A communication protocol allows two or more nodes of a communications system to transmit or exchange data, especially across a computer network. The protocol defines the rules, syntax, semantics and synchronization of communication and possible error recovery methods. Network protocols include mechanisms for device identification and the establishment of connections between them, as well as formatting rules that specify how packets and data are structured in messages that are sent and received. Some protocols support message recognition and data compression, designed for reliable, high-performance network communication. Protocols may be implemented by hardware, software or a combination of both. They are the backbone of the internet and other communication systems, ensuring that information is transmitted reliably and in the correct format.

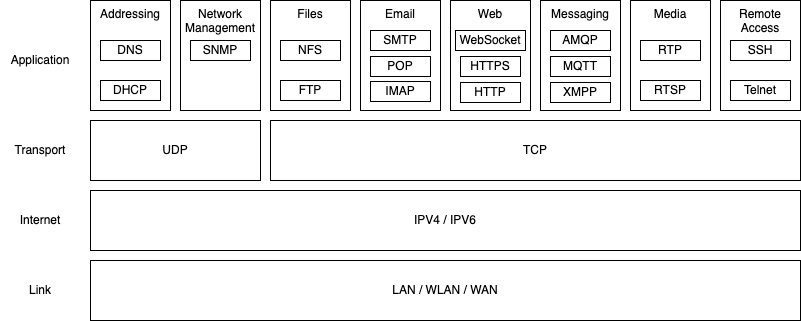

Multiple protocols often describe different aspects of a single communication. A group of protocols designed to work together is known as a protocol suite or family; when implemented in software they are a protocol stack. In the Internet Protocol (IP) suite, the application layer (7th layer in the OSI model) contains the communications protocols and interface methods used in process-to-process communications across an IP computer network. The application layer only standardizes communication and depends upon the underlying transport layer protocols (TCP or UDP) to establish host-to-host data transfer channels and manage the data exchange in a client–server or peer-to-peer networking model.

TCP is a connection-oriented protocol, which means a connection is established and maintained until the application programs at each end have finished exchanging messages. TCP provides reliable, ordered, and error-checked delivery of messages between applications. In contrast, UDP uses a simple connectionless communication model with a minimum of protocol mechanisms, which makes it faster but unreliable. Unlike TCP there is no need to establish a connection prior to data transfer.

Client-Server Communication

Many network protocols are based on a client-server communication model with a request-response messaging pattern. In this model, a server component provides a function or service to one or many clients, which initiate requests for such services. A server host has a public IP address and runs one or more server programs. Each server program is identified by a specific port, which is a number assigned to uniquely identify a connection endpoint and to direct data to a specific service. Clients initiate communication sessions with servers, which await incoming requests. In the traditional pull technology, the client sends a request, and the server returns a response. The reverse is known as push technology, where the server pushes data to clients without client requests. In this model, the client opens a connection to the server and waits for messages. The connection is kept open and the server pushes messages synchronously to the client when it receives them.

Peer-to-Peer Communication

A peer-to-peer (P2P) network is designed around the notion of equal peer nodes simultaneously functioning as both “clients” and “servers” to the other nodes on the network. Peers are both suppliers and consumers of resources, in contrast to the traditional client–server model in which the consumption and supply of resources are divided. Peer-to-peer networks generally implement some form of virtual overlay network on top of the physical network topology, where the nodes in the overlay form a subset of the nodes in the physical network. Data is still exchanged directly over the underlying TCP/IP network, but at the application layer peers are able to communicate with each other directly, via the logical overlay links.

Application Layer Protocols

Application layer protocols provide end-to-end communication between different computational applications. There are many different protocols used in different contexts, each with their own specific set of rules and capabilities.

Communication Protocols

Some of the most common protocols are described in the following table:

| Protocol | Full Name | Description | Applications | Port |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AMQP | Advanced Message Queuing Protocol | Message-oriented middleware, which is designed to efficiently support a wide variety of messaging applications and communication patterns. | Messaging | 5672 |

| DHCP | Dynamic Host Configuration Protocol | Automatically assigns IP addresses and other communication parameters to devices connected to the network. | Network management | 67/68 |

| FTP | File Transfer Protocol | Transfer of files between computers over the network. | File transfer | 20/21 |

| HTTP | HyperText Transfer Protocol | Designed to easily access hypertext documents, which include hyperlinks to other resources. | Web browsing and services | 80 |

| HTTPS | HyperText Transfer Protocol Secure | An extension of HTTP, which uses cryptography for secure communication and is widely used on the Internet. | Secure Web browsing | 443 |

| IMAP | Internet Message Access Protocol | Used by email clients to retrieve email messages from a mail server. | 143/220 | |

| MQTT | Message Queuing Telemetry Transport | A lightweight, publish-subscribe, machine to machine network protocol for message queue/message queuing service. | Messaging, IoT | 1883 |

| NFS | Network File System | Allows a user on a client computer to access files over the network much like local storage is accessed. | Distributed file system | 2049 |

| POP | Post Office Protocol | Used by email clients to retrieve email messages from a mail server. | 109/110 | |

| RTP | Real-time Transport Protocol | Delivery of audio and video over IP networks. | Telephony, video teleconference, TV services, web-based push-to-talk (PTT) | 5004 |

| RTSP | Real Time Streaming Protocol | Designed for multiplexing and packetizing multimedia transport streams. | Entertainment and communications systems | 554 |

| SMB | Server Message Block | Sharing files, printers, serial ports, and miscellaneous communications between nodes on a network. | Microsoft Windows services | 445 |

| SMTP | Simple Mail Transfer Protocol | Transfers email messages from senders’ mail servers to the recipients’ mail servers. | Email sending | 25 |

| SNMP | Simple Network Management Protocol | Collection and organization of information about managed devices on IP networks and for modifying that information to change device behavior. | Network management | 161/162 |

| SSH | Secure Shell Protocol | A cryptographic protocol for operating network services securely over an unsecured network. | Remote access | 22 |

| Telnet | TELetype NETwork | Provides a bidirectional interactive text-oriented communication facility using a virtual terminal connection. | Remote access | 23 |

| WebSocket | Websockets | Provides a full-duplex communication channel. | Chat, social feeds, collaborative editing. | 80/443 |

| XMPP | Extensible Messaging and Presence Protocol | Designed for instant messaging (IM), presence information, and contact list maintenance. | Instant messaging (chat) | 5222 |

HTTP

The Hypertext Transfer Protocol (HTTP) is a communication protocol for distributed, collaborative, hypermedia information systems. HTTP is the foundation of data communication for the World Wide Web (WWW), where hypertext documents include hyperlinks to other resources that the user can easily access. It is used for fetching resources such as HTML documents, images, video files etc. HTTP functions as a request–response protocol in the client–server model. The majority of the communication on the web happens over HTTP, which is not only used for Web browsing, but also as the underlying communication protocol for Web Service APIs (e.g. SOAP, JSON-RPC, XML-RPC, REST, GraphQL, gRPC).

HTTP Request and Response

The most basic form of HTTP is pull mode whereby a client sends a request to a server and the server sends back a response, after which the connection is closed. An HTTP request is made up of the following elements:

- HTTP method, which indicates the action that the client expects from the queried server:

- GET – requests a representation of the specified resource;

- HEAD – asks for a response identical to a GET request, but without the response body;

- POST – submits an entity to the specified resource, often causing a change in state or side effects on the server;

- PUT – replaces all current representations of the target resource with the request payload;

- DELETE – deletes the specified resource;

- CONNECT – establishes a tunnel to the server identified by the target resource;

- OPTIONS – describes the communication options for the target resource;

- TRACE – performs a message loop-back test along the path to the target resource;

- PATCH – applies partial modifications to a resource.

- Request Uniform Resource Identifier (URI), which includes the path to a specific resource on the server machine.

- Optionally, the URI may include request parameters in the query component

- HTTP version (e.g. HTTP/1.1).

- Request headers, stored in key-value pairs, such as:

- User-Agent which identifies the browser or application;

- Connection which indictaes persistent connections (Keep-Alive);

- Content-Type and Content-Length for POST requests.

- Optionally, a body with client supplied data (payload).

An HTTP response is made up of the following elements:

- Response headers, in the same format as provided in the request. These headers provide meta-information about the content of the response, such as Content-Type and Content-Length.

- A body with the content of the response (can be empty).

- A status code that indicates whether the request has been successfully completed. This a 3-digits code, where the first digit indicates the status class:

- 1xx informational response – the request was received, continuing process;

- 2xx successful – the request was successfully received, understood, and accepted;

- 3xx redirection – further action needs to be taken in order to complete the request;

- 4xx client error – the request contains bad syntax or cannot be fulfilled;

- 5xx server error – the server failed to fulfill an apparently valid request.

HTTP Push

HTTP serves most scenarios well, especially when responses are immediate. However, in situations where the server needs to push updates to the client, especially when those updates depend on events not predictable by the client (such as another user’s actions), simple HTTP request-response may not be the most efficient approach. This is because HTTP is fundamentally a pull-based protocol where the client has to initiate all requests.

There are multiple technologies that enable HTTP Push, such as:

HTTP Short Polling

The simplest method of pushing data to the client is based on HTTP Short Polling. In this approach, the client, which could be a web app running in a browser, repeatedly sends HTTP requests to the server. Whenever the server has new data for the client, it will be returned as a response for the polling request. The main problem of this method is that it sends an excessive number of HTTP requests. This takes up bandwidth and increases the server load. Also, data can be pushed only after a polling request has been initiated by the client, which might cause delays.

HTTP Long Polling

With long polling, a client connects to a server, makes a request and waits for a response. After receiving the request, the server checks if it has any new data which has not been already sent to the client. If there is, it sends the data to the client in its response and closes the connection. if there isn’t, it does not immediately send a response but rather keeps the connection open and waits until there is new data to be sent. Only then a response will be sent down to the client. After receiving the response, the client sends another request to the server and the process is repeated over and over again.

Although long polling cuts down the number of requests, each open request still maintains a connection to the server. If there are many clients, this can put strain on the server resources.

Server Sent Events

Server Sent Events (SSE) is a server push technology that enables a browser (client) to receive automatic updates like text-based event data from a server via an HTTP connection. The client establishes a persistent and long-term connection with the server. The server uses this connection to continuously send events to the client. This setup is ideal for situations where the server needs to regularly push data to the client, while the client just receives the data without needing to send information back to the server. A typical example is live stock market data updates.

WebSocket

WebSocket is a communication protocol, providing persistent, full-duplex communication channels over a single TCP connection. Unlike HTTP which is one way (half-duplex), a websocket connection provides the ability for two-way (full-duplex) communication between the client and the server, allowing both sides to send data at any time. WebSocket is designed to work over HTTP ports 443 and 80 as well as to support HTTP proxies and intermediaries, thus making it compatible with HTTP.

HTTPS

Hypertext Transfer Protocol Secure (HTTPS) is an extension of HTTP, which uses cryptography for secure communication and is widely used on the Internet. In HTTPS, the transmitted data is encrypted using Transport Layer Security (TLS) or formerly, Secure Sockets Layer (SSL). The protocol is therefore also referred to as HTTP over TLS, or HTTP over SSL. An HTTPS connection can protect the data transfer from the man-in-the-middle attacks and common security threats by providing bidirectional encryption for communications between a client and server.

Data in HTTPS is encrypted and decrypted through the following steps:

- The client (typically browser) and the server establish a TCP connection.

- The client sends a “client hello” to the server. The message contains a set of necessary encryption algorithms (cipher suites) and the latest TLS version it can support.

- The server responds with a “server hello” so the browser knows whether it can support the algorithms and TLS version.

- The server then sends the SSL certificate to the client. The certificate contains the public key, hostname, expiry dates, etc.

- The client validates the certificate and generates a session key and encrypts it using the public key.

- The server receives the encrypted session key and decrypts it with the private key.

- Now that both the client and the server hold the same session key (symmetric encryption), the encrypted data is transmitted in a secure bi-directional channel.

HTTP Versions

HTTP had undergone significant transformations since its inception in 1989 with version 0.9. The first HTTP release was a one line protocol where GET was the only request method and the response contained only HTML content.

HTTP 1.0 was designed as a browser-friendly protocol with the following features:

- Provided header fields including rich metadata about both request and response (HTTP version number, status code, content type).

- Response: not limited to hypertext (Content-Type header provided ability to transmit files other than plain HTML files — e.g. scripts, stylesheets, media).

- Methods supported: GET, HEAD, POST

- Connection nature: terminated immediately after the response (each request required a new TCP connection).

HTTP 1.0 was replaced by HTTP/1.1, which introduced critical performance optimizations and feature enhancements — persistent and pipelined connections, chunked transfers, compression/decompression, content negotiations, virtual hosting (a server with a single IP Address hosting multiple domains), faster response and bandwidth savings by adding cache support. However, it still couldn’t fix the issue of ‘Head-of-Line’ (HOL) blocking, which happens when all parallel request slots in a browser are filled. HTTP/1.1 also added new methods: PUT, DELETE, TRACE and OPTIONS.

The HTTP/2 protocol differs from HTTP/1.1 in a few ways:

- It’s a binary protocol rather than a text protocol. It can’t be read and created manually. Despite this hurdle, it allows for the implementation of improved optimization techniques.

- It’s a multiplexed protocol. Parallel requests can be made over the same connection, removing the constraints of the HTTP/1.x protocol.

- It compresses headers. As these are often similar among a set of requests, this removes the duplication and overhead of data transmitted.

- It allows a server to populate data in a client cache through a mechanism called the server push.

HTTP/2 solved several problems that the creators of HTTP/1.1 did not anticipate. In particular, HTTP/2 is much faster and more efficient than HTTP/1.1. However, HOL blocking could still occur at the transport (TCP) layer.

The next major version of HTTP, HTTP/3 has the same semantics as earlier versions of HTTP but uses QUIC instead of TCP for the transport layer portion. QUIC is designed to provide much lower latency for HTTP connections. Like HTTP/2, it is a multiplexed protocol, but HTTP/2 runs over a single TCP connection, so packet loss detection and retransmission handled at the TCP layer can block all streams. QUIC runs multiple streams over UDP and implements packet loss detection and retransmission independently for each stream, so that if an error occurs, only the stream with data in that packet is blocked. This effectively eliminates HOL blocking at the transport layer.