Hardware Virtualization is technology that enables the creation of multiple simulated environments from a single, physical hardware system. With virtualization, a single computer system (machine) can run numerous operating systems simultaneously, each with potentially different applications and libraries inside. It is based on the creation of virtual machines that act like real computers with operating systems. Software executed on these virtual machines is separated from the underlying hardware resources.

In hardware virtualization, the host machine is the machine that is used by the virtualization and the guest machine is the virtual machine. The terms host and guest are used to distinguish the software that runs on the physical machine from the software that runs on the virtual machine. These guests treat computing resources like CPU, memory, and storage, as a pool of resources that can easily be relocated.

The software or firmware that creates a virtual machine on the host hardware is called a hypervisor or virtual machine monitor. Virtual Machines rely on the hypervisor’s ability to separate the machine’s resources from the hardware and distribute them appropriately.

Different types of hardware virtualization include:

- Full virtualization – almost complete simulation of the actual hardware to allow software environments, including a guest operating system and its apps, to run unmodified.

- Paravirtualization – the guest apps are executed in their own isolated domains, as if they are running on a separate system, but a hardware environment is not simulated. Guest programs need to be specifically modified to run in this environment.

Hypervisor

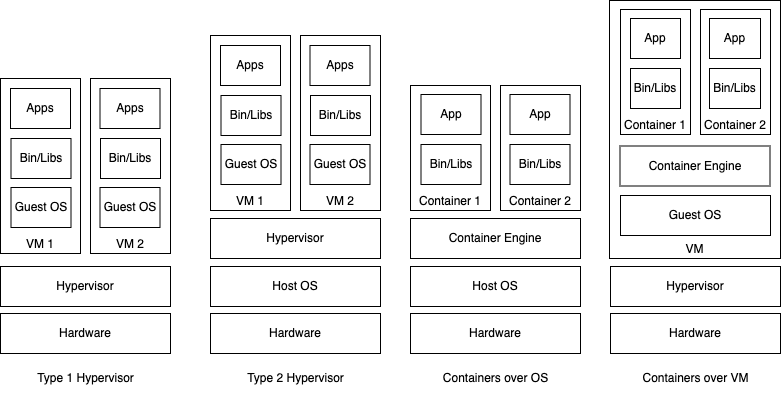

A hypervisor (also known as a virtual machine monitor, VMM, or virtualizer) is a program for managing and running virtual machines, and making sure that they don’t interfere with each other. There are two types of hypervisors:

- Type 1: ‘Bare-metal’ hypervisors have their own device drivers and interact with underlying hardware components directly for any I/O, processing, or OS-specific tasks. A bare-metal hypervisor essentially behaves as an operating system, except that you only really interact with it through the virtualisation tool. This results in better performance, scalability and stability.

- Type 2: ‘Hosted’ hypervisors that run as an application on top of the existing OS of the host machine, and can be started and stopped like normal programs. The host’s OS is responsible for the hardware drivers instead of the hypervisor itself, and is therefore considered to have more “hardware compatibility.”

Some operating systems include built-in type-1 hypervisors:

- Linux includes a kernel-based virtual machine (KVM), a full virtualization solution for Linux on x86 hardware that can run virtual machines directly.

- Windows is shipped with Hyper-V.

Alternatively, you can use commercial products such as VMware ESXi, or type-2 hypervisors such as Parallels Desktop, VMware Workstation / Fusion and Oracle VirtualBox.

Virtual Machines

A system virtual machine (VM) is the emulated equivalent of a computer system that runs on top of another system. It is an efficient, isolated duplicate of a real computer machine. Each VM runs its own operating system (the guest OS), and behaves like an independent computer utilizing a portion of the underlying computer’s resources (the host):

- Computing power, through hardware-assisted but limited access to the host machine’s CPU and memory;

- One or more physical or virtual disk devices for storage;

- A virtual or real network interface;

- Any devices such as video cards, USB devices, or other hardware that are shared with the virtual machine.

If the VM is stored on a virtual disk, this is often referred to as a disk image. A disk image may contain the files for a VM to boot, or, it can contain any other specific storage needs.

OS-Level Virtualization

OS-level virtualization is an OS paradigm in which the kernel allows the existence of multiple isolated user space instances, called containers, zones, virtual private servers, partitions, virtual environments (VEs), virtual kernels or jails. Such instances may look like real computers from the point of view of programs running in them. A computer program running on an ordinary OS can see all resources (connected devices, files and folders, network shares, CPU power, quantifiable hardware capabilities) of that computer. However, programs running inside of a container can only see the container’s contents and devices assigned to it.

Containers

A container is an application bundle of lightweight components, such as application dependencies, libraries, and configuration files. A containerized application runs in an isolated environment on top of a traditional OS or in a VM for easy portability and flexibility. It allows the application to be easily deployed, and run uniformly and reliably across multiple computing environments, such as a personal computer, a traditional IT infrastructure or the cloud.

Containers and VMs are similar in their goals: to isolate an application and its dependencies into a self-contained package that can run anywhere. But, while each VM brings its own OS, containers share the host OS kernel and usually the binaries and libraries, too. As a result, they are more lightweight, you can deploy a lot more at once, and they are low(er) maintenance. Because they share a common operating system, only a single OS needs care and feeding for bug fixes, patches, and so on.

VMs vs. Containers

Containers have two states: rest and running. When at rest, a container is saved as a container image – a file (or set of files) which is pulled down from a registry server and used locally as a mount point when starting containers. There are several competing Container Image formats (Docker, Appc, LXD), but the industry is moving forward with a standard governed under the Open Container Initiative (OCI). This initiative, which was originally based on the Docker V2 image format, has successfully unified a wide ecosystem of container engines, cloud providers and tool providers.

A container engine is a piece of software that accepts user requests, including command line options, pulls images, and from the end user’s perspective runs the container (using a container runtime such as runc, crun, railcar, containerd, Youki, LXC and Kata Containers). There are many container engines, including Docker, RKT, CRI-O, LXD, Podman and OpenVZ. Also, many cloud providers, Platforms as a Service (PaaS), and Container Platforms have their own built-in container engines which consume Docker or OCI compliant Container Images.

Docker containers are the most popular kind of container among developers for cross-platform deployments and it is actually the de-facto standard container management technology. Docker containers use Docker Engine and numerous other container technologies, including Linux Containers (LXC), to create developer-friendly environments that are reproducible regardless of the underlying infrastructure. They are standalone executable packages that include everything needed to run an application: code, runtime, system tools, libraries and settings.